Why do we so often repeat the past? For me, it comes down to comfort. The times I challenge myself to look into a new approach is usually when I hit crisis, meaning “the way I currently behave is no longer working.”

In a previous post, I chronicled the biggest crisis of my career: I almost left the classroom. Essentially, leading up to this crisis, the way I was conducting myself appeared to be “working.” Then, seemingly instantaneously, what I thought was working didn’t work any more.

In that situation, I was confronted with reality, and I either had to change or quit. There was no going back. But there have been other moments in my career where I have stepped back and taken a closer look at what I was doing and asked myself, “Is there a better way to do this?”

When I landed my first job as a teacher, and set foot in my classroom for the first time, my mind was racing with all the big ideas I had for how I would teach the students on my roster. It was decided. I was going to be all of the best traits of my previous teachers minus all the worst traits. Not only that, I was going to be like those teachers from the movies: an inspiration.

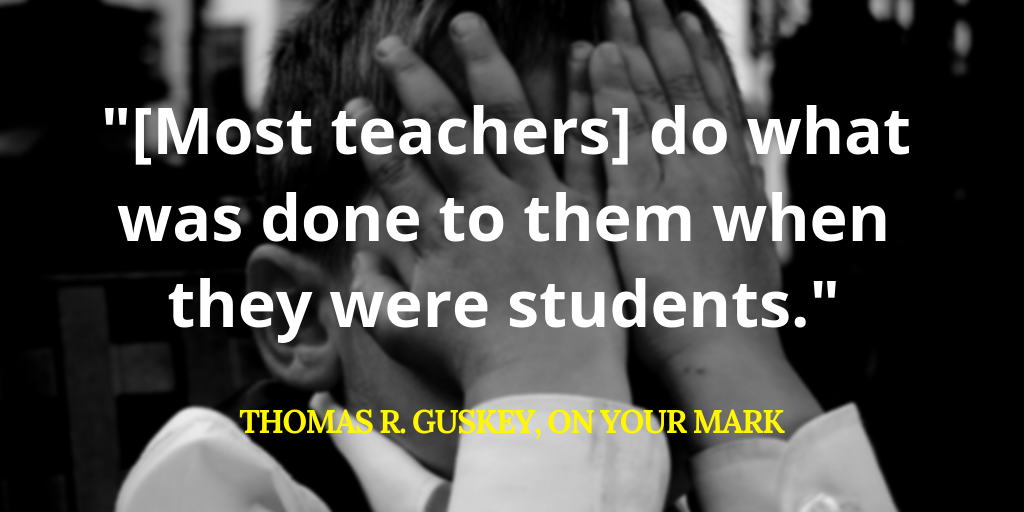

That wonderful yet painful first year came and went. There were ups and downs, high idealism and disillusionment. But most of all, there was a lot of me doing to my students what was done to me by my teachers. When we’re not sure what to do, we go to what’s familiar, even if it’s counterproductive and perhaps even potentially destructive.

There is a term for this phenomenon in the field of psychology: Repetition Compulsion. This is a psychological condition that, when identified, may lead one to engage in several years of treatment. In the article “Repetition Compulsion: Why Do We Repeat the Past,” Kristi A. DeName opens with the following, “Humans seek comfort in the familiar. Freud called this repetition compulsion, which he famously defined as ‘the desire to return to an earlier state of things.'” Further down the page, she clarifies her definition:

It could be that many of us develop patterns over the years, whether positive or negative, that become ingrained. We each create a subjective world for ourselves and discover what works for us. In times of stress, worry, anger, or another emotional high, we repeat what is familiar and what feels safe. This creates rumination of thoughts as well as negative patterns in reactions and behaviors.

While repetition compulsion is typically discussed in connection with destructive patterns in relationships, I couldn’t help but notice some striking parallels between my early experience as a teacher and DeName’s description. Though repetition compulsion is a psychological term, I find it fitting to apply it to the instructional practices I embraced early in my career. For better or worse, I did to my students what was done to me. Can you blame this teacher? I didn’t have any experience in the classroom except as a student.

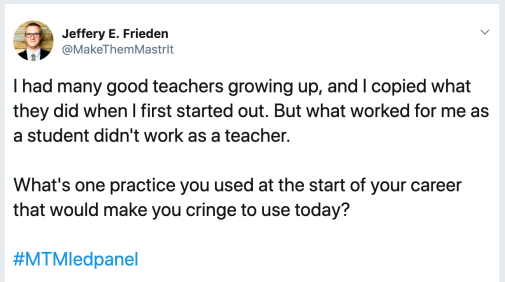

Last month, in a post on Twitter, I posed the following question:

The conversation that followed was engaging. And depending on your beliefs and background, may even be considered controversial. At the time of this writing, there were 53 replies, many of which branched off into discussions of their own.

From that Twitter thread, I have compiled a list of my favorite habits that teachers have kicked to the curb and are no longer doing to their students what was done to them by their teachers.

1. LECTURE & COPYING NOTES

45+ minute lectures! My throat grows sore just recalling the days that I would talk at my students all period long, cajoling them into copying what I had bullet listed on a PowerPoint slide deck. I remember, a few years in to the job, during the first couple of weeks of school, I would stock up on hard candy and ingredients for home remedies to nurture my inevitable sore throat as I got back into “speaking shape.”

And when it came to note taking, I was guilty of simply having my students copy the notes. I wouldn’t teach them note taking strategies, giving them opportunities to learn how to learn. Instead, I would just keep them busy scrawling whatever was on screen, forbidding them to take pictures with their cellphone cameras. (If you’re looking for various and more productive ways to have students take notes, then see Cult of Pedagogy’s posts HERE and HERE).

Am I saying lecture is inherently bad? No. It depends on how a teacher approaches the oldest of instructional strategies. But the combination of a longwinded lecture accompanied by slides of bulleted lists that the teacher insists students copy needs reconsideration.

While reading recently, I came across a term I had not heard before: interactive lecture. Instead of luring students into a somnambulant submission of slowly recording an instructor’s slide deck on paper, teachers could (and should) punctuate their lectures with student interaction throughout (after 5-7 minutes of talking). Students can think-pair-share, participate in a quick standing quiz, or develop some agency by choosing partners to talk with using the Ongoing Conversations protocol.

2. COMPLIANCE-BASED READING ASSESSMENT

“How do I make sure my students to do the assigned reading?” I cannot think of a more essential question when assigning a text, whether it’s in language arts, social studies, or science. Any class where students are assigned a text to read–especially if the reading is expected to be completed after school–has a teacher puzzling over how to encourage those students to take ownership for engaging with the text in a meaningful manner.

Here are some of the ways my teachers checked up on my reading:

- A regular diet of reading quizzes

- An assigned packet of questions

- Answering chapter questions

- Note taking

- Gotcha questions in the middle of a lesson

Most of what we call “reading instruction” is centered around catching students not reading rather than challenging them to read to learn.

— Aaron S Blackwelder (@AaronSBlackwel1) May 23, 2019

When I first entered the profession, these were the practices that I deployed regularly. And, when I thought about it, they did not inspire a love of reading for me when I was a student. I did the required reading for the grade.

Over the past decade, I have heard many teachers lament, “They just don’t read anymore!” I don’t think that’s accurate. I’ll admit that there are fewer and fewer students motivated to fulfill the requirements of reading that is merely assigned. But the problem is that they are not inspired or encouraged to read, especially if there are other modes that allow them to access the learning assigned by the teacher (i.e. YouTube, podcasts, audio book, etc.).

We need to face the situation, acknowledge what’s really happening, look at the opportunities we have in our classrooms, and seek an alternative that works for both teachers and students. Assigning, then setting up structures in the classroom that catch students when they are not reading is not developing the kinds of readers we hope to develop.

3. THE OVER-POLICING OF CELLPHONE USE

Though this is not about instruction, cell phones certainly have the potential to interfere with classroom learning. I find it tempting to call for an outright cellphone ban, but that approach would be an over reaction. Is the problem the phone?

My experiences and observations have brought me to the point where I see technology, especially the tech that’s on our cellphones, acting as an accelerant for what’s in the heart. What I mean is, I use technology to do help me do things I already want to do. The cause of any problems that I have while on my phone comes from me–I am the source of the problem, not the phone.

Totally hear you. And, use this exact point to facilitate an empowered discussion about such obsession and addiction. Empowering kids to observe their own behaviors/thinking and monitor their presence in each moment is a life skill I value tremendously.

— Julia Fliss (@JuliaFliss) May 23, 2019

Let’s imagine that a law is passed that bans cellphones in schools, and the next time you hold class, students will show up phoneless. To what extent is this helping them manage their longings and desires? Sure, it will free up their focus during school hours. But will they be better stewards of their phone usage overall? I don’t think so. It’s just delaying the problem until after school hours.

My take is that we need to help students negotiate life with a that powerful piece of technology they have in their pocket. Maybe could start with this video from Edutopia:

4. NEEDLESS QUIZZING

Even though this one appears to have been addressed with compliance-based reading assessment, this one gets an honorable mention here. Before my powers of reflection were developing as a teacher, I thought I had to be quizzing because that’s what I needed to do.

The types of quizzes alluded to in the Twitter thread were those discrete bits of instruction that are taught, but some of us struggle to assess. Items like spelling and vocabulary.

Instead of quizzing as a way to hold students accountable, what if we had students engage in no-stakes retrieval practice? This can be done in student partners or the teacher calling on students at random. Keep it simple, save yourself from having to mark and score those items, and they need not impact a students’ final mark in your class.

5. PUNISHING ACADEMIC NON-COMPLIANCE

You know what I’m talking about. Those little things that make assignments neat and tidy so that we can mark their papers just a little bit faster. I used to hold points hostage in my classroom for students not correctly writing out an MLA heading on their papers. Sometimes the only strategy we think we have at our disposal is to punish, to take things away, if the students do not conform to our procedures.

Oh, that first one hurts.

— Jeffery E. Frieden (@MakeThemMastrIt) May 23, 2019

When I started to reflect on my participation in this practice, I started to notice that there were far fewer students breaking with the format than I had previously thought. When my strategy was set on catching students stepping out of line, it was putting highlighter on those issues, making them stand out.

But really, when I stepped back and looked at the sum total of students who found their own way of formatting, they were few and far between. At a certain point, I simply started to talk with those students and do what I could to bring them in closer alignment with stated expectations. I was more relaxed, and the students were still learning.

6. GRADING EVERYTHING

Are you a teacher who thinks you need to grade every assignment (big or small) that your students complete? If you are, I get it. I used to be that teacher. It nearly drove me out of the classroom forever. I would experience guilt over the work that wasn’t getting assessed, which caused me to spend too many hours outside of my contract grading it all. Then I would feel guilty about not being present at home with my family. It was a dance with shame, and I am happy to say I am free of it!

It’s time to stop the madness. Teachers, you do not need to, nor should you, grade everything your students produce. Not only is that too much pressure on you, it’s added pressure for your students. There are low- and no-stakes ways students can produce work for a class without the teacher having to mark every piece and enter it into the grade book.

If you’re a teacher looking for ideas that can start you on a path to marking fewer and fewer assignments, head over to teachersgoinggradeless.com. There are great, practical, resources there for thinking through how you can mark fewer assignments.

7. DOING MORE = RIGOR

As a young honors and Advanced Placement (AP) teacher, I fell into this trap. There was this assumption that honors students showed they were honorable because they did more work. Also, I must confess, teaching honors was my first experience in an honors environment. I was never an honors or AP student myself. Did I admit this to my students and colleagues? Of course not! I just pretended like I knew what I was doing and assigned tons of work.

My first year teaching AP, there was a break in the calendar looming, and I got all sweaty thinking that I had to assign something. I ended giving my students this absurdly long vocabulary assignment. When the students returned from break, they dutifully turned in the assignment. One witty student titled his document “Spring Break Busy Work Vocab Thing.” I chuckled and said, “I like your title.” He took it as an opening to critique the assignment, which he claimed “taught me nothing, but kept me really busy.”

Ouch! But… he was right. For the first time, this got me thinking that honors needs to be more than just stressing out my students. I started asking around, reading, reflecting, and evaluating the opportunities that present themselves with honors students, and things have really improved.

But this is not a lesson solely for honors teachers alone. I have attended my fair share of faculty meetings where we have been instructed that we need to increase rigor, and after a review of one of the various graphics for Hess’s Cognitive Rigor Matrix or Webb’s Depth of Knowledge, hints are dropped that teachers should respond by assigning more work.

So, what is rigor? I like the following definition by Brian Sztabnik, which can be found at Edutopia’s post, “A New Definition of Rigor”:

Rigor is the result of work that challenges students’ thinking in new and interesting ways. It occurs when they are encouraged toward a sophisticated understanding of fundamental ideas and are driven by curiosity to discover what they don’t know.

The words that resonate with me the most in that definition are “challenge,” “new and interesting,” “encouraged,” “curiosity,” “discover.” When I want my students to engage in rigorous learning in my classroom, I should be asking “How can I engage my students’ curiosity by encouraging and challenging them to discover new and interesting ideas, connections, or applications of their learning?” It turns out that “more work” is never the answer to that question.

Breaking the Pattern

How do we stop ourselves from doing to our students what was done to us when we were the pupils? Answering this question is especially difficult when we are comfortable with what we are doing in our classes.

Since those early days of teaching, I have found ways to re-calibrate, adjust, or replace each one of the practices above. Some were easy to give up; others proved to be a bit more of a challenge to let go of.

One way a teacher can break from a comfortable pattern is to ask, “Is what I’m doing in class helping my students toward their goals?” If the answer is “yes,” then the next question a teacher should ask is, “Are there are more effective ways I can help students reach those goals?” If there are, then maybe it’s time to break the pattern.

QUESTION: How about you? When you first started teaching, what was done to you as a student that you did to your students as a teacher that would make you cringe to do today?

The point of repetition compulsion is not that one should break a harmful cycle that we as humans revisit because it was done to us so we just blindly repeat it. The point is to understand that ‘pleasures’ are momentary and there is a deeper thing humans seek, a satisfaction in excess, transgression and things that are not good for us. There is no “enjoyment” without damage or exploitation. “Enjoyment” happens at an unconscious level, the level of “trieb” or “instinct” or “drive.” It’s certainly not about seeking patterns of “comfort” in what is familiar to us. The “death drive” is a blow to Aristotle’s longstanding contention that we seek that which we think is good. To understand people and our world, we have to think differently than this, we have to understand the satisfaction one gets out of repeating behaviors that are obviously not “good” for us or others. Presenting repetition compulsion as a nostalgia for the past is taking Freud’s work on emancipation and repackaging it in an ultra conservative, Right Wing fashion.

LikeLike