I’m going to make a prediction that you might not like. After reading this post, you’re going to see that you are doing rubrics all wrong.

But that’s okay. I had bad rubrics for years too. In spite of their poor quality, my students were still learning. Yours are too. But maybe our students at that time did not really feel like learners. There was a time when the rubrics I used to score my students’ assignments made them feel like losers.

Several years ago, when Carol Dweck’s book was taking American education by storm, I took a long look at my practice and asked where I was promoting a fixed or growth mindset. Also around that time, I was reading books like John Hattie’s Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning and Thomas Guskey’s On Your Mark: Challenging the Conventions of Grading and Reporting. All of the combined insights from these influential educators shined a light on the rubrics that I was handing my students. To put it nicely, those rubrics were limiting — focused more on describing how poorly the students were performing rather than pointing out the good things they were doing.

And another thing. I started to pay attention to the design of my rubrics. And the more I looked at them, the more offended I became. Read on to find out more.

The Two Main Problems with Rubrics

In short, here are the two problems with rubrics:

Problem #1: They lack clarity to inform students of what they did, or did not do, in their work.

Problem # 2: They are designed to communicate student deficits, not student competency.

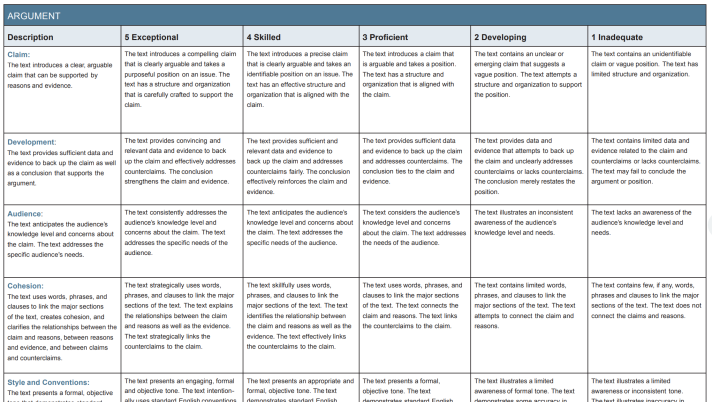

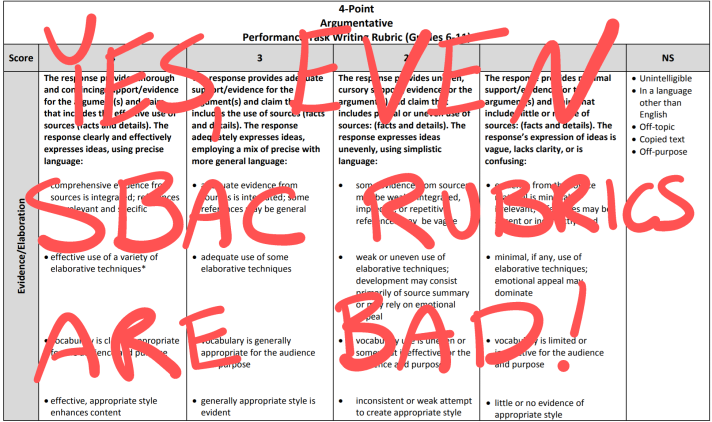

For problem #1, let’s take a look at a bare-naked example that took the categories of the Argumentative CAASPP Performance Task Rubric, and turned it into an analytic, itemized scoring guide:

At a glance, you can see this is a typical analytic rubric. The assessment categories are on the left, the descriptions of each level are on the right (which descend from high to low). If you’re like the old me, when starting a complex assignment, you would give the students a prompt and then the rubric that shows how the assignment is to be assessed/scored.

There were times that I would take the students through the whole rubric to explain each part, maybe even show examples of each category. Perhaps you have done the same. But just take a second and look at all that text in those tiny little boxes. Are students really paying attention to this? Not. At. All. (By the way, this is only ONE part of a three-part rubric!!!)

But that’s not the problem. Let’s assume your students dutifully pay attention to the rubric instruction. They get the basics (categories first, good grade on the left, bad grade on the right). They work hard on an assignment, you mark up a rubric, and then the day arrives when they will receive their feedback. They get the marks, but they are having trouble understanding what they mean because it’s full of qualitative descriptors:

Let’s say that a student was marked as “Developing,” which to me means that they are “on their way” and are “really starting to get the hang of it.” So, what does this student’s claim look like? The rubric reads, “The text contains an unclear or emerging claim that suggests a vague position.” What does that even mean? I’m not sure, but when the student reads this descriptor, it probably doesn’t feel like he or she is “developing.” It probably feels more like he or she is “disappointing” the teacher.

Let’s move down the list. Next is development (as in, how the ideas were put together, not the “developing” from the assessment category . . . does anyone else’s head hurt?). Here the student is confronted with this, “The text provides data and evidence that attempts to back up the claim and unclearly addresses counterclaims or lacks counterclaims.” What is an “attempt” to back up a claim? And which is it? Did the student lack a counterclaim or just unclearly address one?

I could go on, but let me highlight my favorites from this snap shot:

- What is the difference between a “compelling” claim and a “precise” claim? Doesn’t that depend on audience, rhetorical situation, and type of argument?

- “Convincing and relevant” vs. “sufficient and relevant”?

- For the low-scoring description in the “claim” category, it reads, “The text contains an unidentifiable claim or vague position.” I wouldn’t know how to describe a “vague position” to a student, but how does a scorer even know that a text “contains” an “unidentifiable position.” If it is “unidentifiable,” how does a scorer recognize that!?

Basically, the lower-scoring writers who were in my class, the ones who needed the most help, were the most confused in the evaluation of their writing. And even the students who scored high on the rubric really didn’t know what they did to earn that score.

The heart of the problem is that scoring columns use adjectives to describe an elusive quality in student writing. There is no discussion of what the student writer DID and what kind of impact it had on a reader. It’s not feedback that is helping the students adjust their academic behavior to improve their competency. It’s just vague description that justifies a score, which makes the teacher feel he or she is being fair to each student since the same assessment tool was used to evaluate every student.

All they see is this:

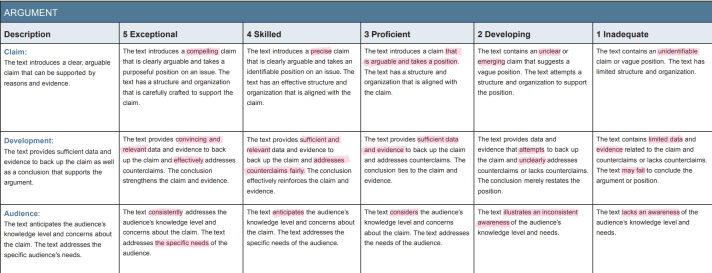

And this leads us to problem #2: rubric design. Reading a rubric like this, from left to right, communicates deficit. If a student understands that the good stuff is on the left-hand side of the rubric, and the teacher marked a lower score, their sense in their own competence will wane as they scan from left to right to discover which box was marked. With all of the positive adjectives on the left and increasingly (or is it descreasingly?) condescending adjectives on the right, the communication is subtle: you must be perfect to maintain a top mark.

But none of us are perfect. We also know that none of our students are perfect. Yet the design of our scoring tool continues to reinforce this myth that that students need to be perfect. If they’re not perfect, then they are losers. This does not focus on a student’s growth, but focuses on their inability to accomplish a task at the level of proficiency.

How Can We Fix These Problems?

A Small Fix

One simple change we can all make right away is to simply flip the columns. Leave the category on the left but step-increase the scoring columns from low-to-high. This still leaves the problem of vagueness, but it is at least a better design that moves from bottom to top. It’s the minimum, but it may impact everyone to rethink how they are perceiving the scores. And that can have a big impact.

A Bigger Fix

The best change you can make to an analytic rubric is to get away from adjectives that describe the quality of the product you want from your students. Instead, just describe the behavior you want to see, then mark when you see it.

Here’s an example of a simple scoring guide that I use for an assignment I have named “The Second Draft Entry”:

As you read this scoring guide, you can see that I am describing the academic behavior I want to see from my students. I describe what they need TO DO to earn each score. Each scoring column to the right assumes the behavior from the left, which means that students cannot accomplish the tasks described on the right if they have not accomplished the tasks on the left.

Also, you’ll notice that there are peculiar items in the scoring guide: 2DE (which is just my short-hand for Second Draft Entry), Meta-Margin, and the sentences frames. These are terms that relate directly to how I teach my students about their metacognition when moving their writing from a first draft to a second draft (see this post for more details). These terms have been defined, explained, and exampled for them. They also have handouts as resources. Either they know what I want from them, or they have the resources to figure it out.

The Best Fix

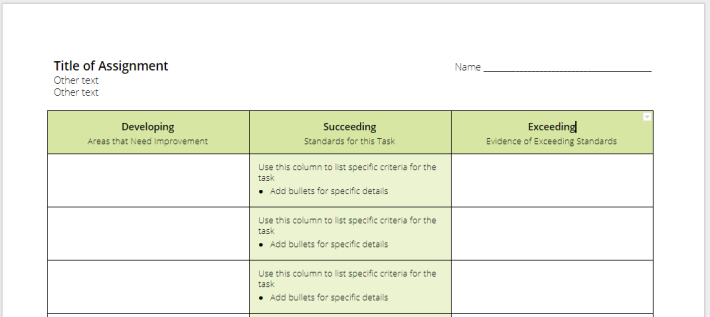

If you’re going to use an analytic rubric, don’t use a grid. Instead, use a single-point rubric. I first learned about the single-point rubric from Jennifer Gonzalez (@cultofpedagogy) of www.cultofpedagogy.com. She gives an excellent description and a key example or two. Do yourself a favor and check out the above links, or “Your Rubric Is a Hot Mess,” where she did a guest post for Brilliant or Insane.

To sum it up, instead of creating an itemized, analytic rubric that tries (but fails) to describe all the academic behaviors a teacher will encounter in a given assignment, the single-point rubric defines the key academic behavior you’re looking for, and defines it at the level of proficiency. It’s laid out in three columns: Developing, Succeeding, Exceeding (at least those are the words I use). Only the middle column (succeeding) contains the clearly defined academic behavior. The columns on the left (developing) and right (exceeding) are left blank for assessor comments.

Here’s a template:

That’s all there is to it! The goal, for you and your student, is to not have to make comments, unless it’s on the right (which means they are exceeding the expectation, and you are rewarding them with atta-boys or atta-girls). But if you do comment in the “Developing column,” the feedback is targeted, specific, and will help your student move up to proficiency.

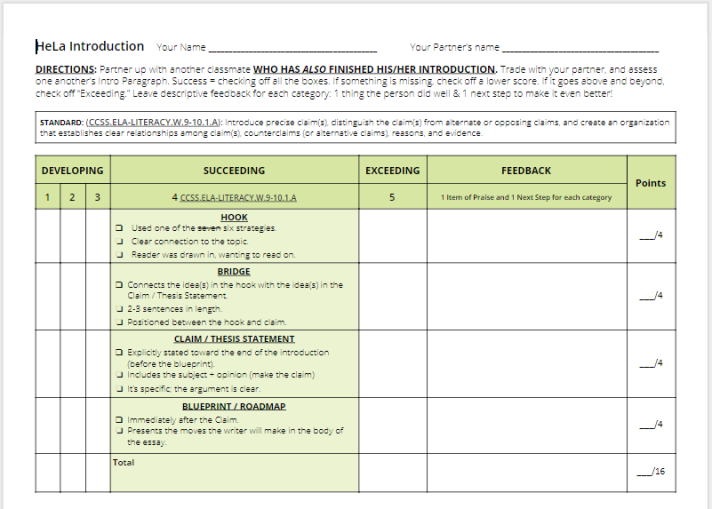

I was able to start incorporating the single-point rubrics into my classroom this past academic year. Of course, I started with the most complex writing assignment my students would face under my teaching. But I thought that it was simple enough to understand that I used them for peer-feedback on the first draft of their inquiry-based argumentative essay based on reading selections of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot. I took the same basic idea of the single-point rubric and modified it, adding a layer of complexity. Here’s what it looked like for my students’ introduction paragraph:

I worked with another teacher on this assignment, and she said that this rubric was amazingly helpful for peer-to-peer grading. The students were very clear on what they needed TO DO for this writing assignment. And the feedback they received from their peers helped them write a better second draft.

Here are the links to all the single-point rubrics I used for this essay:

Now you have what you need to get started, let’s make the world of rubrics a better place for all of our students. Design your scoring guides so that your students feel like they are growing in their competency as learners. Inform them of what the academic behavior they are exhibiting and give them targeted feedback to reach proficiency and beyond!

Question: Do you need to make adjustments to your rubrics?

If you haven’t already, like the Make Them Master It Facebook Page and follow @MakeThemMastrIt on Twitter. I can’t wait to talk about how we can increase the impact we can have on our students!

I inadvertently did a version of the single-point rubric with the 4th graders I was teaching at the end of year. It worked amazingly well because they knew where to shoot. 😊 Your version makes me very happy. I plan to implement this rubric version this next year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome! reach out if you have questions. I would love to help!

LikeLike

Awesome! What a great job stepping us through the fixes! Made the switch to SPRs two years ago and it has been a benefit to all. My next post on summary sheets will feature one.

LikeLike

This is a thought-provoking post and I thank you for sharing it. I will revisit it and parse it some more as I consider the use of rubrics in my classroom. My first reaction is that it really doesn’t have to be either-or — a grid rubric (bad) and a single-column rubric (good). There are lousy grid rubrics and great ones; there are lousy single-column rubrics and great ones. I think you hit the nail on the head when you noted that many students don’t seem familiar with the criteria nor understand it, especially the weaker ones. This can be remedied in two effective ways that I have seen: Using models, self-assessment, and through co-constructing criteria.

First: Models. In my classroom, we spend time (thought perhaps not as much as we should) reading rubrics and having them play teacher, asking them to assess anonymous models of work against the rubric. They usually do this individually and in pairs to discuss their rubric choices. I find the students uncannily accurate in this work. Our rubrics are written specifically by our team for assignments, so our descriptors are pretty specific (e.g. “Demonstrates a sharp ability to read critically. Excellent, cogent evaluation of the effectiveness of author/artist and his/her overall aim. Consistently references relevant outside research, providing insightful context. Illuminating connections to themes, course Essential Questions, and big-picture ideas. Excellent level of interest and engagement with the text. Makes the reader say: “Wish I’d thought of that.”) With this kind of specificity in the descriptors, we find that students can usually see pretty clearly when it’s happening in a sample text and identify when a writer does it well or not so much.

Second: Self-assessment. Then, we ask them to assess their own work — both for formative, no-count assessments (just for practice with the same rubric) and on summative essays they are about to submit. We want students to always assess themselves before turning in their written work. Seeing them underline the rubric descriptors before we take a look often helps us understand if they have an accurate sense of their work each time or if they are way off — either far too generous or too tough on themselves.

Third: You can co-construct the rubric with the students, which I have seen done in several classrooms by using great, professional and student writing as the guide for great organization, voice, language, etc. look and sound like. Students write the descriptors at each level by using these models, another way to get familiar with criteria and own it.

While none of this guarantees better writing, it does really help to move students to much deeper understanding of criteria and knowing better where they stand in relation to it on any given assignment.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for taking the time to share your thoughts. There is a lot to go through here. And more competent teachers than I have spent many years thinking this all through. My stance in this post is not as radical as others out there. Alfie Kohn and Maja Wilson come to mind. Both would love to throw rubrics out entirely. I’m not quite there yet, but those two are making more and more sense to me with each week that passes.

There are some presuppositions that lie behind why I think analytical rubrics are not good for students, and not good for teachers either. In my post, I was directing most of my ire at analytical rubrics that describe (very poorly) the quality of student work. I advocate that if a teacher make any changes at all, it’s asking the students to exhibit a learning behavior, as in “to get x score, you must exhibit x behavior.” It’s clear to the student if he or she has hit the mark. Getting to the point, the problem with an analytic rubric is that as a teacher, I am trying to capture all the potential behaviors that a student may exhibit in their learning for a particular assignment (let’s say an essay). If I sit down with say four categories and I want to reduce the behaviors in four gradations, I have already set limits on what the learning should look like on this assignment. Once I fill in the grid, I have set the boundaries for how the learning must be exhibited.

Now, let’s say I give the students the prompt and the rubric. I help frame how they should approach the writing, and I guide them through the process. When they submit their essays, I will assess their learning (in this case their writing). But since I have set clearly defined expectations and trained the students, I will not really assess the quality of their product. I will be assessing how well they conformed to my expectations for this assignment. If a student was inspired to write a letter to my prompt, even though I was asking for an analytical essay, then I will demonstrate how that student failed my assignment. But the letter has a quality all its own, and the student should get feedback on that, as well as a conversation about why he/she chose that medium instead of the one assigned.

When I am quite literally busying myself with the task of putting student learning into boxes, then I am missing their development as learners.

It’s better for me to give them a single point rubric that is open ended on either side, and tell them how they are moving past the expectation, or how they are falling short. Instead of looking at a 16 boxes of potential feedback and trying to comprehend it, they are looking at four, seeing how far off, right on, or how much beyond they are in their learning.

But I am starting think that even this is too constricting. I just don’t know another way. Even Kelly Gallagher is looking for a way to rid his writing assessment of rubrics (https://twitter.com/KellyGToGo/status/946035678877442048). I want to as well. I’m just not sure of the next step.

Maybe I should do a series of posts? (This is a rough-draft thought)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have you read this post by Sean Michael Morris? https://www.seanmichaelmorris.com/subjectivity-rubrics-and-critical-pedagogy/

LikeLike

I saw your comment on a Dave Stuart post which prompted me to view your blog. I really thought your discussion on rubrics, examples, and purpose were quite enlightening and I intend to use this system with my students. Thanks for the easily accessible material on Google docs and I will let you know how it goes. Nice, impressive work here! Congrats!

LikeLiked by 1 person